Millbrook Alumni Summit

Last week, I had the honor of sharing my story with young professionals in New York City (thanks Danny Mitchell and Michael Kanner for hosting an amazing event) and Millbrook students at the annual Alumni Summit. Here is what I said:

“A few days ago, on my morning run, I listened to a podcast about the challenges young American men are facing today. Our culture raises men to believe their value is tied to money, and 74% of suicidal men used the words “worthless” or “useless” to describe their dark thoughts.

As I heard this statistic, I crested a hill in the rain, feeling the weight of my soaking backpack, cars honking and whizzing by, and I broke into tears. I was thrust into the lowest moments of my runs through Canada and Africa and remembered that they were my exploration of what it means to be a man. I felt frighteningly alone at times and questioned what my value to society was.

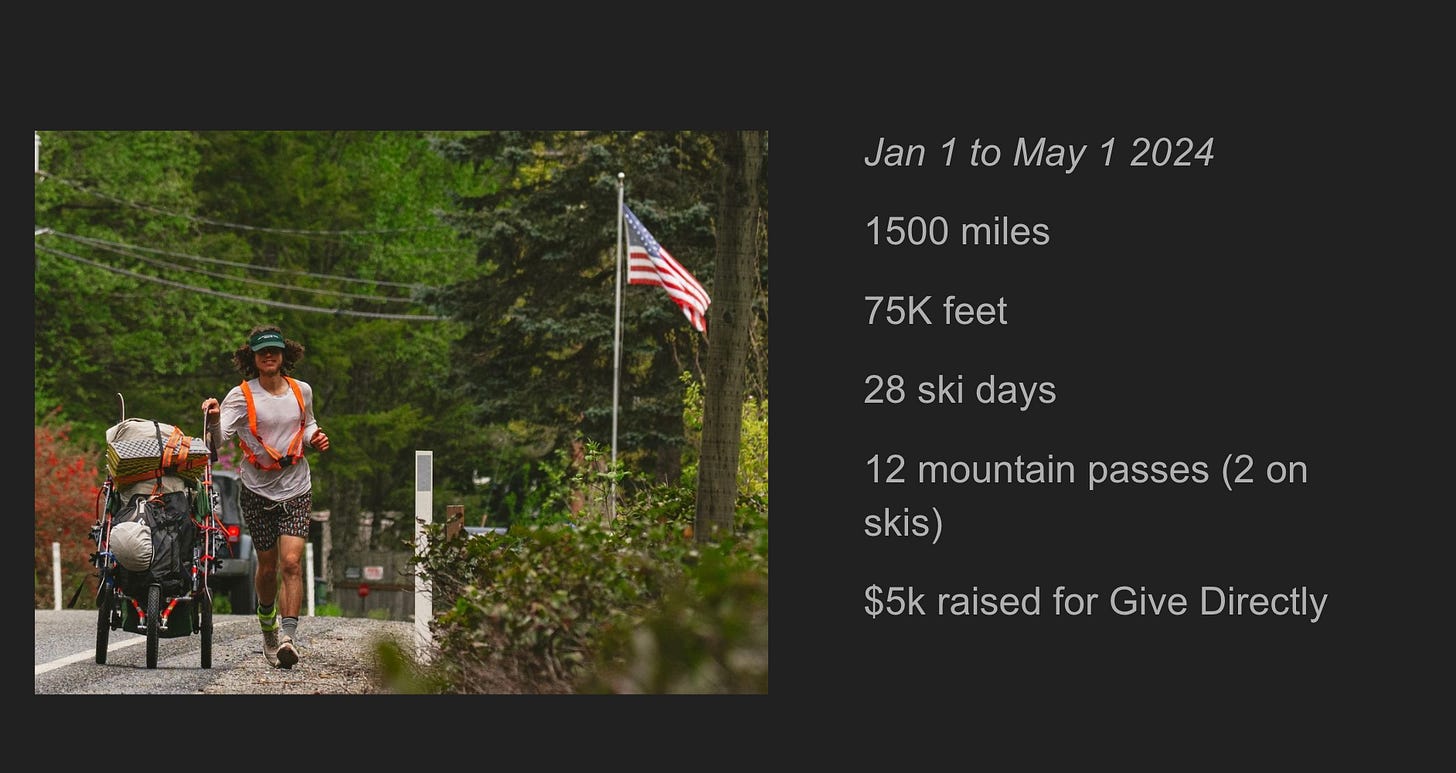

On Monday January 1, 2024, I started running from my front door in Seattle pushing a baby jogger with my camping gear and skis. I had no idea where I would end up or when I would stop running, but there was no turning back. I had moved all of my things into a storage unit and left my key on the porch on my way out.

I was 25 years old, and 2 months earlier, I got fired from my job as a software engineer at Amazon. Six months prior to getting fired, I had finally closed the door on my nomadic post-college life (or so I thought) to move into a house with people I loved in a city I loved. I was going on dates. I ran or biked to work everyday. I was “settling down” and loving life.

Yet, when I got fired, I felt an adventure coming. I visited a man named Gar to spend four days fasting and meditating on his land. Gar said to me, “If there’s something in your heart that you know you want to do, do it, and do it fearlessly.”

Two guys had just climbed the 100 tallest mountains in Washington in a single summer biking between each peak. I loved the concept of a “human-powered” adventure, and my friend Matt Montavon ran the entire length of Alaska, north to south, pushing a baby stroller in 2011.

My idea was to do a winter human-powered adventure running with my skis across the west. I wanted to see what my body was capable of and do something that filled my soul at the end of each day.

I found a baby jogger on Craigslist (I still keep in touch with Glen who sold it to me). I started going on test runs with it around Seattle. I strapped my skis, then I fit my boots, then all my winter camping gear, clothes, and finally took it grocery shopping to buy food.

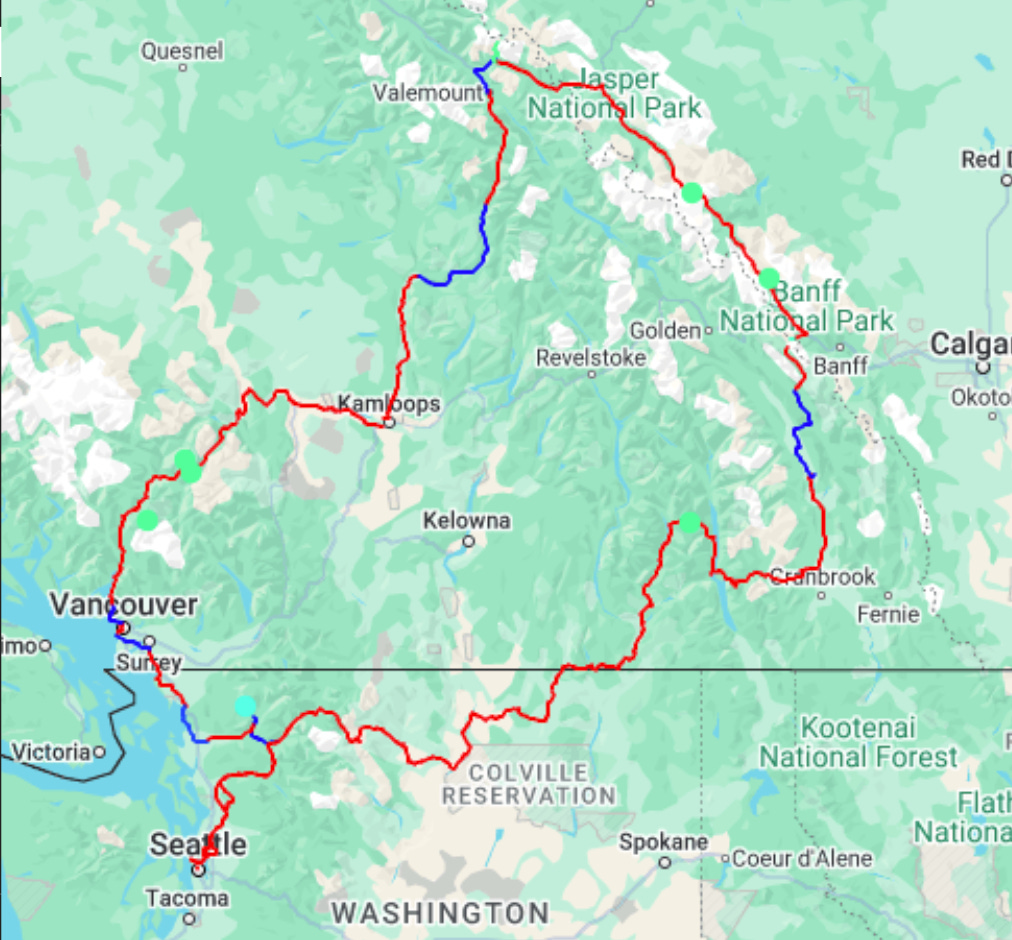

When January 1 (my chosen start date) came around, the only thing I hadn’t gotten around to doing was map out a route. No matter, I set my sights on the Methow Valley, the first place I fell in love with in Washington State. My first day I ran 20 miles. I was tired and sore, but my body felt good. At the end of the week, I rolled into Marblemount, the last town on highway 20 before North Cascades National Park.

I had run 100 miles, camped in sketchy places, run past “Trespassers will be shot” signs, and fixed flat tires in the middle of nowhere. I was proud, but my body was destroyed. I had never run so many miles. I took a rest day, and when the time came to start running again, I stared at my stroller paralyzed with anxiety. A cold snap had come bringing 0ºF temperatures and storms in the mountains. I called my friend Lukas. He talked me back to sanity and helped me decide to change my plans.

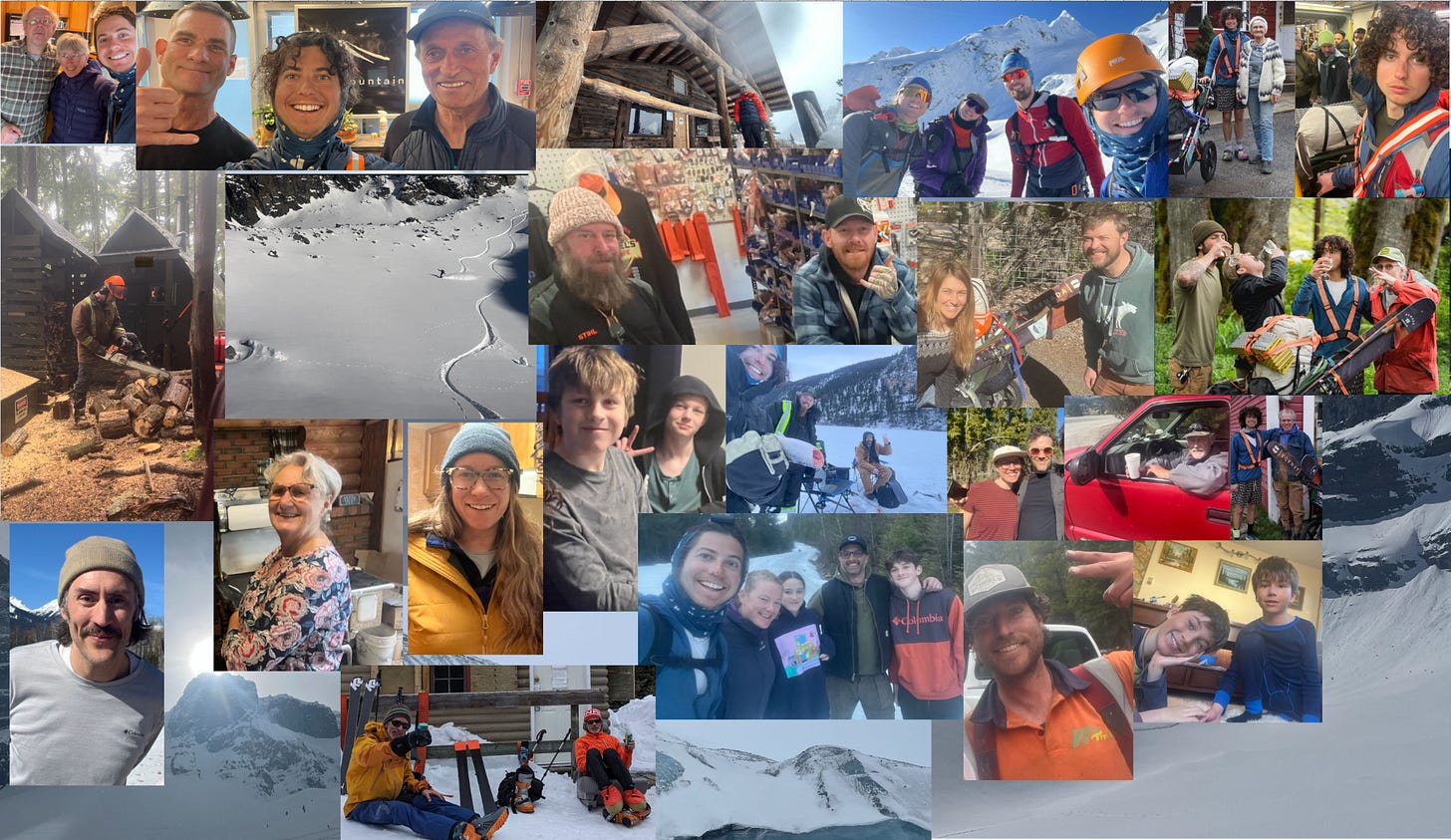

Later that day, I made friends with a local, Devin, who let me stay with him to wait out the cold snap and recover. When I started running again, I switched course and ran for Vancouver, Canada. Over the next two months, I would go on to push my body to its breaking point two more times.

The final time happened after running through Whistler, Pemberton, Lillooet, and Kamloops all the way to a little town on the edge of the Canadian Rockies called Clearwater. I was weak and starting to get sick by the time I arrived at 89 year-old Jean Nelson’s house. Jean took notice of my sad state and encouraged me to take a break. She called Lee Onslow, the mayor of the next town up the road who agreed to host me. Jean braved the winter highways to drive me 100km to the Onslows’ house.

When Lee greeted me at the door, she told me, “You can stay as long as you need.” I went straight to the bedroom and slept for 14 hours. The next day, I went to the town’s pick up basketball game, and it took all of my effort to hide my grimaces as I hobbled around the court chasing kids. I lacked motivation to run and considered giving up the whole adventure. But, over the course of a week with the Onslows, I made daily use the hot tub, joined the family to go snow-mobiling, and watched the Lord of the Rings trilogy with their kids, Richard and Grayson.

Lee ended up writing a letter to my mom, in which she wrote that she was proud for her kids to meet someone like me. Hearing that a mother wanted her kids to know me reminded me why I set off on the adventure in the first place. Re-inspired, I decided to try running one more time and continued north. The first night I camped on the side of the highway in temperatures below 0ºF.

I ended up making it to Jasper, Alberta, then ran and skied the full length of the Icefields Parkway, and eventually made it back to Seattle for my birthday a month and a half after leaving Jasper. I had run a complete circle and more than doubled my pace on the way home. In the end, I ran over 1500 miles, climbed 75K feet, and crossed 12 mountain passes, two of which on skis towing a sled with my stroller behind me.

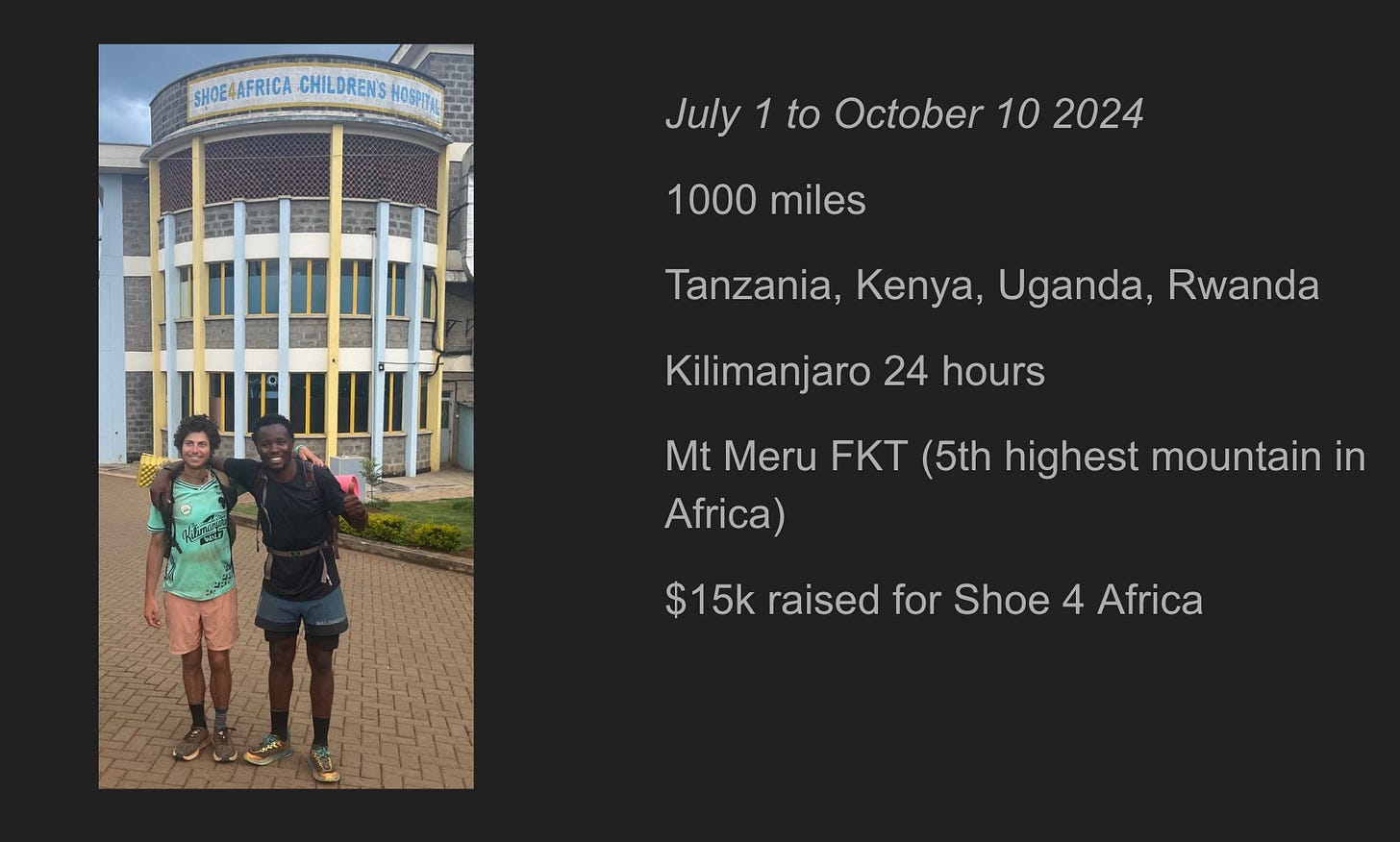

When I finished, I was excited about what I had done and curious to see what else I could do. I committed to another run, and for my family safari to Africa in June, I changed my flight to a one-way ticket.

At the time, a guy named Russ Cook was already running across Africa. I loved Russ’s YouTube videos and aspired to make my own. My sister Lizy agreed to produce them, so I sent her footage everyday from my runs. Masoud, my translator, instantly became the star.

I met Masoud on the first day of my run about 20 miles inland from the Indian Ocean. I had arrived in a small town called Muheza and used Google translate to ask for someone who spoke English. A young 22 year old guy showed up and plunged straight into deep existential conversation.

“Why are you doing this?” Masoud asked. For fun. “No, I need to know the truth because you are successful, and I need to be successful for my family.” I tried to explain I wasn’t successful and that I was paying for this trip with unemployment checks. Masoud said, “So the government is paying you to do this? Are you a spy?” Unemployment assistance is not a concept in Tanzania. At one point, Masoud asked if I believed in God. I said, “I don’t know. Do you?” He said, “No, I believe in fighting on the streets.”

And that’s exactly what he’d been doing. No family in town, he was crashing with friends, standing on the street to pick up cheap labor jobs, eating one meal a day, no money to his name. Until that point, I thought I went to Africa to inspire people, but Masoud showed me that I came here to get inspired. I asked him to come with me as my translator, and he ended up joining me all the way to Kilimanjaro. (Now he’s back in school thanks to my mom and grandma for paying his tuition.)

The next unexpected source of inspiration in Africa came during my toe infection. The night before my planned Kilimanjaro climb I woke up with a throbbing pain in my toe. I yanked out a thorn with pliers, and the toe infection that ensued sidelined me for over a month. While recovering in Moshi, I met a motorbike taxi driver named Living. He lived in a small village in the foothills of Kilimanjaro outside town. I asked if I could stay there with his family to recover.

He said yes, and I upgraded from an empty guesthouse to sharing a cot with Living in a small concrete house with a single light bulb. I was surrounded by family— grandparents, Living, his wife, Living’s brother and his wife, and three young kids. I went on morning runs up towards Kilimanjaro and eventually learned about the poor folks in Living’s village struggling to eat just one meal a day.

I had come here to put one foot in front of the other, and if I couldn’t move myself maybe I could try to move others. I had the money to buy food for hungry families. It seemed simple enough to buy in bulk and deliver it to them. I didn’t know if this would necessarily be impactful but felt like it would lead to good things. Later, my climbing guide Rocky agreed to absorb the project into his NGO and continue delivering food. Now, the project has evolved into building chicken coops for families.

My toe infection also earned me a partner because it delayed the rest of my run until after Tanzania’s tourist season. Rocky decided to spend his break running with me from Kilimanjaro through jungle, desert, fields of zebras and giraffes over the Kenyan border, the rest of the way to East Africa’s only public children’s hospital.

One day, running through Maasailand, a man started chasing me with his spear. I ran faster, and when he saw the fear in my eyes, he started laughing. It was the first and only time in Africa I met a man while I was running who didn’t fear me at all. Fittingly, the Maasai have been embroiled in a decades long battle with the Tanzania government to preserve their traditional way of living in mud huts herding goats and cattle.

On the day Rocky and I were meant to arrive at the hospital, I woke up in a bad way with severe stomach issues. I could barely walk with a backpack let alone run. Rocky carried both our packs and still outpaced me. At one point he got far ahead, and rain started pouring down. I yelled at the top of my lungs, “Rocky! Wait!” When I finally caught up with him, I exclaimed, “Rocky I really don’t feel good! Please slow down!” He smiled and said, “Oh! But I feel great!” I couldn’t help cracking up despite seething with frustration.

When we finally arrived at the hospital the following day, I met Toby Tanser the man who built it. He gave me a tour, and when we got the playroom, he said, “Sorry I need to go to a meeting. Do you mind if I leave you here?” Suddenly, I found myself sitting awkwardly in a room full of kids, feeling like the left out kid instead of the superhero I wanted to be for the kids. One girl walked up to me and started setting up a memory card game for us to play. Without exchanging any words, we started playing together. She whooped me.

Two other kids joined. None of them had any idea that I ran to the hospital and wouldn’t have cared anyway. They had visible tumors in a region of the world where 9 out 10 kids with cancer pass away within 5 years. And yet, they were the ones who made an effort to be kind to me in this room. Again, I was shown that I came to Africa not to be a hero but to find heroes.

The following week, I found myself in Iten, “Home of the Champions,” a town where many of the world’s best marathon runners train. I stayed with a local athlete named Peter.

Each morning, we woke up early for training. By 8am, we were done with the day’s work and had the day to relax until evening run at 5pm. The athletes were like lions: wake up sprinting and spend the rest of the day sleeping. I never learned how Peter earned money, but to this day, he represents the most exciting model of fatherhood to me that I found in all my travels.

His 2 year-old son Ryan would run around the house and start crying when he hit an obstacle like the stairs. I noticed myself thinking that his son was too needy and demanded too much attention. But instead of getting angry Peter would smile and go help Ryan. All day, Peter and Ryan would meander around town; they would visit the neighbors, play in the yard, and walk around aimlessly.

I realized Peter was doing this, not to try to be a great father, but because he simply enjoyed spending time with Ryan. He had no smartphone, no job, so Ryan was his only form of entertainment. Until meeting Peter, I didn’t know that it was possible for a father to spend so much time with his kids. I had always imagined myself having an important job and going off to work everyday.

But Peter’s energetic glow and smooth confidence could have matched any Fortune 500 CEO. Peter showed me that I don’t need prestige or money to feel valuable as a man. I can simply do what I love fearlessly.”