How to Run with the Ugandans Pt. 2

Olly’s Note

I’m on the bus from Munich to Basel, Switzerland. In Munich I spent two days with Pascal and two days with Max and Christina, all friends I met in Canada. On a run yesterday, Christina reminded me of how, in Canada, the blog centered on all the people who treated me with kindness on the road. She loved reading about random acts of good humans in the world. What made the adventure special was that it was human-powered!!

Now feels like an especially prescient time to appreciate the goodness in the world, and I have relied on a lot of it lately to survive in Europe on a tight budget. In the last two weeks, Georg and Yella adopted me as their second son with Vincent, and then Sebastian and Marina made Vienna feel like home. In Munich, Pascal brought me to his stomping grounds in the Alps where we had an alpine hut to ourselves until a military helicopter landed there for a drill. Back in town, Christina gave a yoga class that rekindled my joy for the discipline, and introduced me to Curry Worst (sausage with curry flavored ketchup 😋).

Recap: In the lead up to this post, I ran from the Shoe 4 Africa Hospital in Eldoret, Kenya to the Uganda border. Lacking motivation to run my first day in Uganda, I called my friends Lukas and Daniel, who helped me decide to switch plans to searching for the pro runners of Uganda. The following day I was living with Uganda’s current fastest 1500m runner, Daniel Kiprop 😉. Click here to read part 1 of How to Run with the Ugandans.

Please enjoy!

September 28, 2024

Daniel Kiprop and I settled into a routine living together. He never asked for payment, so I bought daily groceries and other household items.

I became fascinated with visiting a mountain village 10km from Kapchorwa called Teryet. As the site of Uganda’s new National High Altitude Training Center (NHATC) and Joshua Cheptegei’s NN camp for the country’s most promising young runners, I thought Teryet must be the best place for training. Joshua Cheptegei is the undisputed king of running in Uganda (and arguably the world) right now, and he hails from Teryet. Cheptegei holds the world record in the 5km and 10km.

Daniel claimed that Teryet wasn’t actually so great for training because it’s cold and rainy, but he agreed to take me there. While he dislikes Teryet for training, Daniel loves a medicinal drink called Lakwek that locals there make from roots in the forest. Supposedly, Joshua Cheptegei himself drinks Lakwek after training; locals say it gives you energy and flushes the toxins from your body.

Daniel borrowed a motorbike and drove us 10km up the road to the NHATC. From what I could find online, the construction of the NHATC has taken over 10 years, cost the government millions of dollars, and remains behind schedule due to corrupt contractors and officials (big shocker).

What we saw was a nice track and turf field that resembled a standard high school football field in New Jersey. Constructed atop a hill at 2550m (8500ft) in elevation, the track has beautiful views but is exposed to wind and surrounded by Mt Elgon’s rainforest. The guards asked for a bribe to let us in. When I showed them my empty pockets, they let us go anyway. Walking through light rain on the empty track illuminated by floodlights felt like entering a dystopian world.

Until the end of my time in Kapchorwa, I never met a single runner who personally uses the NHATC for training. Even NN team’s coach noted that the track is rarely used, “It’s availability is its strength but because it is at such a high altitude there is less oxygen available which can make it tough for athletes to train at.”

After a lap around the track, Daniel took us to the Lakwek. We sat inside a traditional circular mud house with a straw roof. I remarked that the home resembled the Kalenjin houses in Kenya. Daniel responded, “This is a Kalenjin house.”

I looked at him confused, “What do you mean?”

“I’m Kalenjin too. Everyone here is Kalenjin!”

The Kalenjin are the tribe in Kenya famous for producing the world’s fastest runners. It turns out that Uganda also has about 270,000 Kalenjins (compared to 6.5 million in Kenya) who got partitioned when the borders were drawn. Just like Kenya, most of the pro runners in Uganda are Kalenjins!

I sipped the Lakwek and exclaimed, “This tastes like wine!” He said it wasn’t alcohol. I didn’t believe him. The drink was clearly fermented. Daniel pointed to two men who had been drinking Lakwek all night, “Look at them. Are they drunk? No. This is a medicine.” Still skeptical, I drank my bottle. To neutralize the acidic taste, the locals add honey harvested from wild bees in the forest.

After the Lakwek, I felt amazing. My mood improved, and my body hummed with energy. I wondered if it was the same effect as an alcohol buzz, but my mind was sharp as a knife. Wow this stuff is jet fuel! Daniel said we could buy more to take home. It would help us recover after training. The honey tasted so good that we bought a whole liter before riding back home through the cold wet night.

September 29, 2024

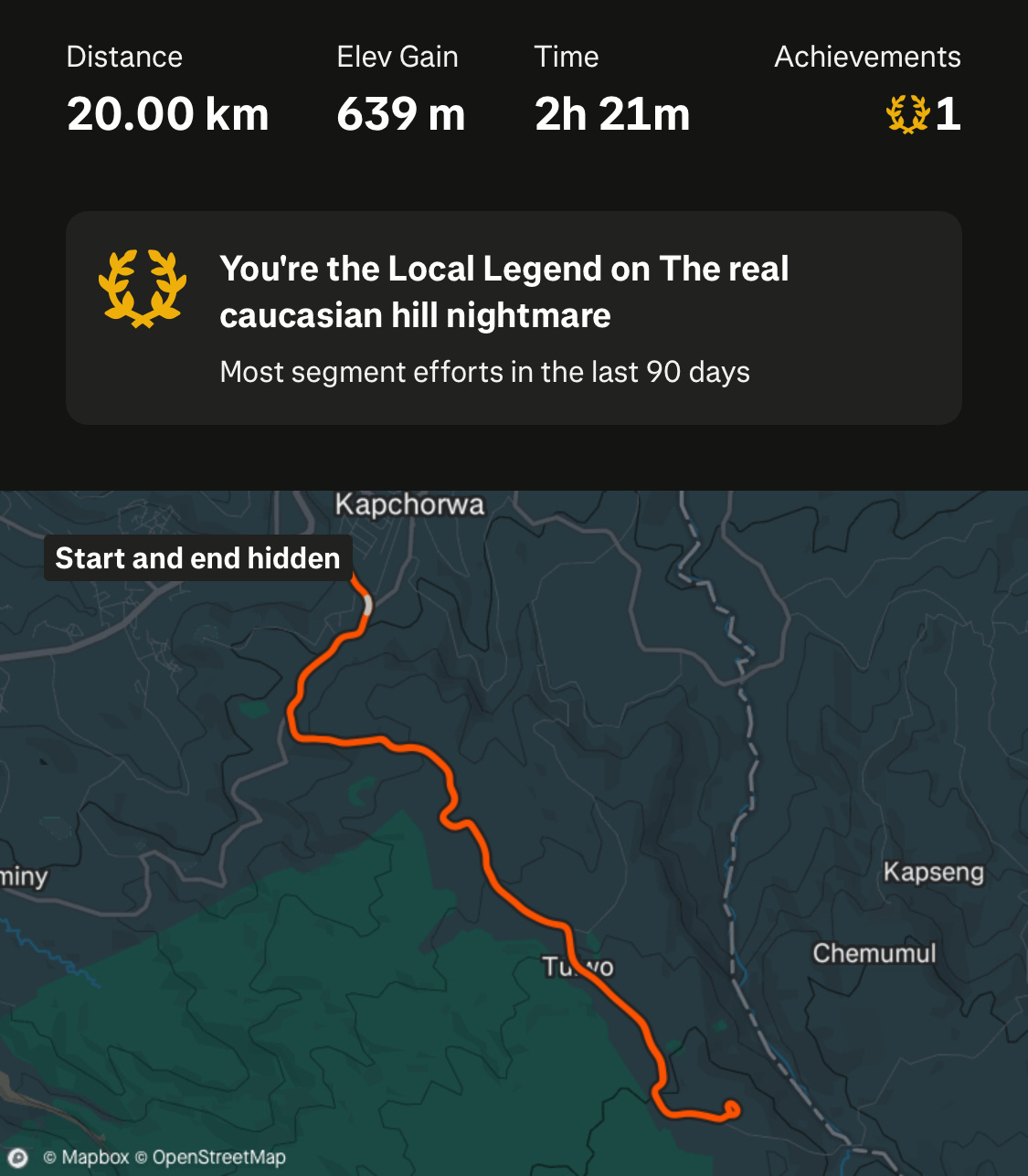

The next day, I still felt off with the training. In Iten, the harder I ran, the stronger I got. Here in Kapchorwa, the harder I ran, the more my body hurt. We’d been running on pavement. With the start of rainy season, many of the dirt roads got too muddy for training runs. I tried to cover the same mileage I did in Iten, but the roads were also more hilly, making each run take longer.

At night, I confessed to Daniel that my hip was bothering me a bit. I didn’t think it was getting better. He told me that was normal here in Kapchorwa unfortunately. “Do you remember the way runners straggled in so slowly your first morning?” he said. “They’re all hurting. Many of them have to skip evening training or the next day because they run too hard on the paved roads and injure themselves,” Daniel continued.

Connecting the dots, I said, “Aha! That’s why the athletes here seem sad.” I didn’t understand why the athletes would choose Kapchorwa as their base if the training environment caused injuries. Daniel clarified that the elite athletes with access to a car drive 25 minutes to sand roads that don’t get muddy in the rainy season. But the grand majority of runners were stuck on the paved roads around town.

In contrast, Daniel told me about a town called Bukwo where his wife and children live. Hold up, you have a family bro? I thought I’d been living with a 23 year old student who might go to Colby college next year. I would soon find out I had yet to meet the real Daniel Kiprop. He proceeded to describe a place with endless flat sandy roads, abundant sun, beautiful forest trails, and a community of happy, confident runners.

Huh? So why aren’t Uganda’s best runners training there. Well, it turns out some of them are. But until last year, there was no paved road to Bukwo! Before the road was completed, the mud road connecting Bukwo to the rest of Uganda often got washed out in the rainy season. It could become impassable for days at a time. Consequently, professional athletes who trained there ran the risk of getting stuck before their races in other countries. Now that the road is paved, Daniel Kiprop believes that all the training camps will have moved there in a few years time.

“So, can we go there?” I asked.

“Yes, if you want,” Daniel said.

“Can we go tomorrow?” I asked.

“Yes, no problem,” Daniel said.

Onwards!

Hello Olly, i want contact with you, greetings Elke - Arusha