Glacier Peak Winter Ascent

The following is the culminating essay in a five part series on some winter adventures.

The following is the culminating essay in a five part series on some winter adventures. You can watch my video version of the trip on Tik Tok. Eric Gilbertson’s account, which gives the strict play-by-play, can be found here. My account is less of a play by play.

February 7: Get Ready for Gilbertson

January 19-25: Washington Ice Climbing with Dan

February 1-2: Solo Winter Storm Overnight at Crystal Mountain

February 4: Mt: Rainier: Longmire to Muir with Peter

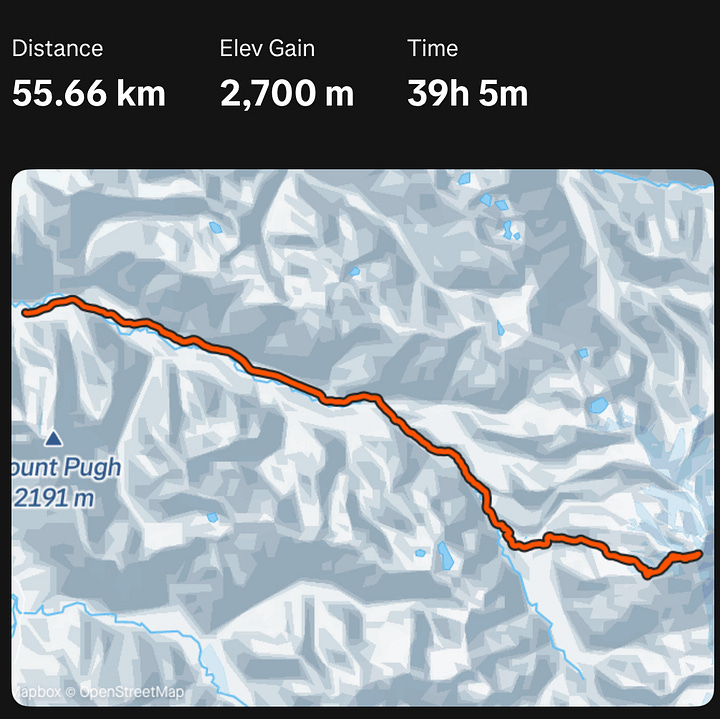

THIS ISSUE 👉 February 8-9: Glacier Peak Ski Descent

My friend Dan went to a “4-minute mile” summer camp when he was in high school. The entire purpose of the camp was to teach youth cross country runners how to run a four minute mile. On the first day of camp, the coach had D1 college athletes crank out 4-minute miles on a track so all the kids could see it happen.

The idea behind the D1 athlete demonstration was “see it to believe it.” If you’ve seen it with your own eyes, then there can be no doubt in your mind that it’s possible.

As a D1 runner is to the 4-minute mile, Eric Gilbertson is to winter mountaineering. Gilbertson can crank out huge climbs involving heavy logistics, miserable approaches, multiple sports, snow camping, sleep deprivation, and atrocious weather like it’s his job (and well, maybe it is if his employer brags about it).

Thus, in going out with Eric Gilbertson, my hope was to witness how someone manages a huge physical endurance push like my runs in Canada and Africa while also solving a complex problem.

Climbing a mountain in the backcountry might be more like mathletes than you think (disclaimer: I know nothing about mathletics). Collect tons of inputs— time, current location, terrain hazards, weather hazards, avalanche hazards, distance to destination, current speed— then twist your brain into a pretzel calculating risks and likelihood of successfully climbing the mountain. Make any necessary adjustments to minimize risk and maximize likelihood of success. And then recalculate and readjust over and over.

So, the question we’ve all been waiting for… Did I witness greatness the weekend of February 8? The answer is an undeniable yes.

The most challenging part of the entire trip for me was not the climb up the peak but rather the approach to the climb. While you can drive to most trailheads in Washington in the summer, the same trailheads might be blocked by 10-20 miles of unplowed forest service roads in the winter. For us to reach the climb, we rode a snowmobile 4 miles down a forest service road, skinned a mile further down the road after it washed out, then skinned a couple miles down another decommissioned forest service road, until reaching the old trail, which itself washed out after a couple miles.

From the trail wash out, we rappelled into the river basin and posthole dover rocks for several miles. As I poured my attention into maintaining my footing in ski boots while carrying a heavy pack, I would glimpse Eric float across the snow over logs, stop to check the map, think about the next move, eat a snack, drink water, and start floating again before I caught up to him.

My morale ebbed and flowed with each turn in the river, but Eric remained steadfast. He never once indicated a sign of weakness, discomfort, or loss of confidence. I had to hide my surprise when he asked my opinion in decisions. I realized that Gilbertson cared only about using the best possible judgment, and two brains provided more processing power than one. He displayed no trace of ego or valuing his ideas more than mine. He was only interested in finding the best solution to the equation (I’m liking this mathlete analogy).

I often imagine running as a meditation with the mantra of using spare attention to focus on the body and form. With Gilbertson, the mantra seemed to be: use spare attention to calculate risk and think about the next steps. In the end, both mantras have the goal of using the least possible energy to move forward.

The climb left me even more fascinated than before. I had watched magic unfold in front of my eyes, but there was no trick. This was Gilbertson’s 81st Winter Bulger— his 81st time solving for a summit that rarely or never gets climbed in winter.

One thing that continues to stick in my mind was Eric’s urgency to get back to Seattle. He leads a perfect double life, professor of mechanical engineering by weekday, and winter mountaineer by weekend. When he is home, Eric meticulously plans the logistics of the next climb. Then, in the mountains, Eric uses every second to get back to Seattle as fast as possible.

This became clear to me in the 37th hour of our push, I had run out of energy and food and realized that my speed would be up to my mind. I imagined that I was running and started gliding faster across the snow. Eric commented approvingly that I sped up.

I felt like I had transcended my body and achieved an altered mental state. In my trance, I asked Eric, “Do you imagine that you’re running while you’re skinning in order to go faster?” Expecting a profound answer, Eric replied simply, “I usually check the time and see when I have to get back to Seattle.” He couldn’t have been more matter of fact, and the answer shattered my world.

Even though Eric Gilbertson does intense multi-day adventures more consistently than anyone I have met, the way he talks about them paints a picture of someone minimizing time in the field, not maximizing it. I now speculate that this is the only way a double life could sustain itself long-term. I have a feeling that as my own life progresses, I will have to fight harder to get into the mountains, and also fight harder to get back home as soon as possible.

When he dropped me off in Seattle, I told Eric I’d be psyched to go out with him again and could make myself available any weekend left in the winter. A few weeks later I followed up again, and he offered the final weekend of winter, March 15-16. I was determined to come back faster, stronger, and ready to soak up more knowledge.

TBC